At Siteman Cancer Center, a new clinical trial is underway that will evaluate the benefits of a neoantigen vaccine in combination with chemotherapy and immunotherapy to treat small cell lung cancer (SCLC). The rapidly growing, aggressive cancer represents about 15% of all lung cancers in the U.S.

SCLC has low survival rates, with most cases diagnosed when the cancer has spread to other parts of the body. For more than 40 years, the standard treatment has been systemic chemotherapy. Over the past few years, however, immunotherapy has become an option. Recently, two large clinical trials have investigated the use of monoclonal antibodies that block a specific immune inhibitor called PDL1 and found that a small subset of patients can benefit from this type of treatment and have long periods of remission.

Now, Washington University researchers at Siteman are going a step further and, for the first time, are evaluating a personalized neoantigen vaccine for SCLC. The clinical trial is open to certain patients newly diagnosed with SCLC who have not yet begun treatment and who do not have brain metastases.

“In trying to improve immunotherapy responses, there are a few things we know,” said Jeffrey Ward, MD, PhD, the study’s principal investigator and a Washington University medical oncologist at Siteman. “In particular, as a consequence of smoking, lung cancer cells have a lot of mutations in their genetic code. These mutations generate tumor-specific antigens called neoantigens that the immune system can pick up on. By identifying and then going after these neoantigens, we hope to educate the immune system and stimulate it to have a more robust response to attack the cancer.”

It’s a highly personalized approach based upon each patient’s own DNA and part of a one-two punch against SCLC. The key is obtaining tissue biopsies before current therapies are started so oncologists can sequence the DNA and develop a specific neoantigen vaccine for each patient.

“It’s critical to see newly diagnosed patients before they begin treatment,” Ward said. “But once we get the biopsy, patients can immediately begin standard treatment at their cancer center, which is chemotherapy and durvalumab, an FDA-approved immunotherapy drug.”

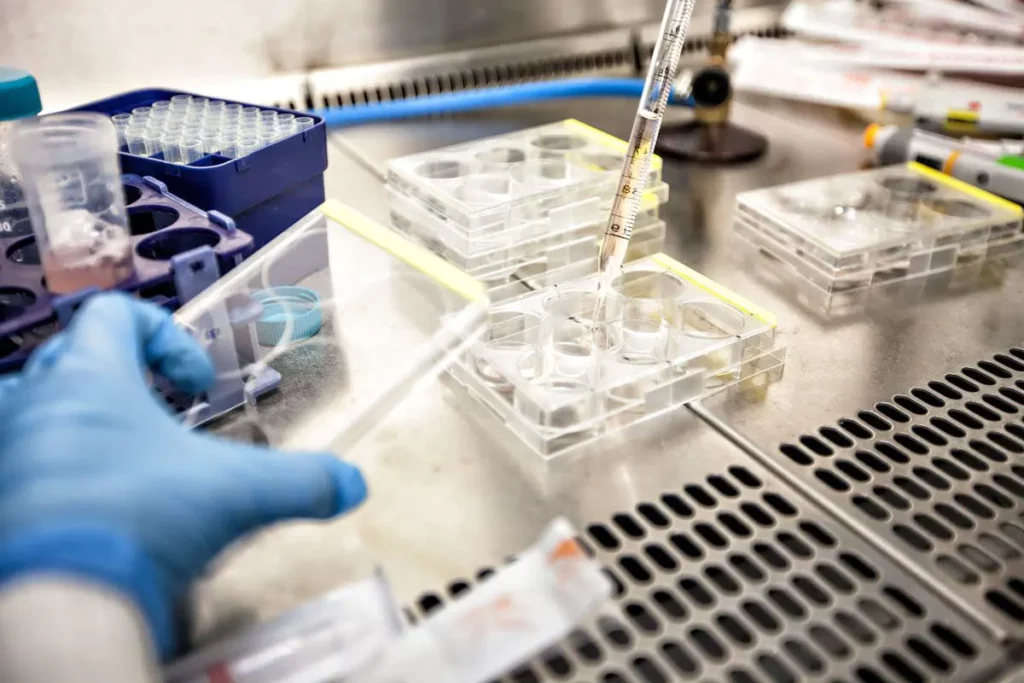

It takes about 16 weeks to sequence the DNA, identify specific mutations and then manufacture the personalized neoantigen vaccine, which is done at Siteman’s Biologic Therapy Core Facility together with the laboratory of William Gillanders, MD. Gillanders, a Washington University surgeon at Siteman and vice chair of the Department of Surgery, researches neoantigen cancer vaccine development.

“We have similar neoantigen vaccine trials at Siteman that focus on other cancers, such as breast and pancreatic cancers as well as glioblastoma,” Ward said. “There also are other clinical trials here for patients with extensive stage SCLC whose cancer has spread despite treatment.”

Investigators at Washington University are at the forefront of studying gene alterations in lung cancer. Based on their groundbreaking SCLC research three years ago, they won a competitive grant from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to study the mechanisms of resistance to cancer therapy.

“The neoantigen vaccine study represents the ultimate personalized medical therapy based on each patient’s tumor characteristics and represents the best example of translation from laboratory research to clinical research to help our patients with lung cancer,” said Ramaswamy Govindan, MD, the principal investigator of this research project. Govindan is a Washington University medical oncologist and the Anheuser Busch Endowed Chair in Medical Oncology.

Added Ward: “I think there’s a critical message to highlight, too. Cancer treatment continually evolves. The best time to look into treatment options is at the very front end — immediately after diagnosis — because patients can enroll in some of the most advanced clinical trials before treatment begins.”